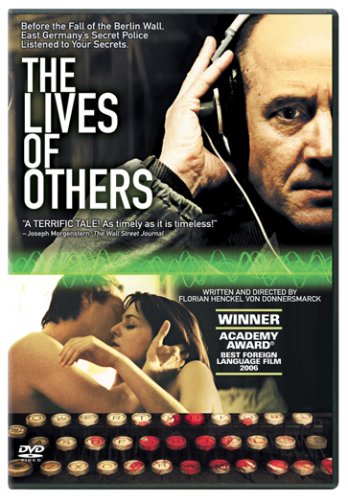

For Christmas, my sister (who blogs at MissionIncomplete) gifted me the movie The Lives of Others (henceforth referred to as LoO, because I’m lazy at typing and LoO is a funny-looking acronym.).

Based on what came up when I googled it, it’s a fairly popular movie in the U.S., for a foreign film. It’s German make, directed by Florian Henkel von Donnersmarck, and came out in 2007.

Though it came out in 2007, this feels like an old movie, and I mean that in the most complimentary manner possible. I don’t mean the acting was cheesy and the set chintzy. It felt quiet, and if films had souls, this one’s soul would be old.

Though I’ve only ever seen five foreign films in my life (at most), this one followed the pattern of the ones I’ve seen. Foreign films seem to be, in general, quieter than American productions, probably because, as we learned in film class last year, while here film is primarily entertainment, in Europe it’s more of an art form. The soundtracks especially seem to be less dramatic and overbearing, and the colors are often subdued. I think, for certain stories, such as A River Runs Through It (Robert Redford, 1992) and October Sky (Joe Johnston, 1999), it conveys the message better with a quieter tone. Some messages require a light hand to deliver them. Some hands, such as the one that made The Lives of Others, are so light, I don’t really know what the message even is yet.

Though I don’t know what this movie is rightly saying, I can praise it no less highly. Forgive me for taking until the fifth paragraph to give you the synopsis. It is about East Berlin, before the Wall fell, and follows a playwright and a member of the Stasi (secret police), who watches him. It gets extensively into how the Stasi monitors people, and captures the oppression of that quite well. Initially, the playwright is above suspicion, but a corrupt government official falls for the playwright’s girlfriend, and so orders his house watched, so that maybe they’ll find something incriminating and can jail the playwright, and thus the official can have the playwright’s girlfriend. Additionally, the playwright is a bit of a political liability, thought he hadn’t been watched before. That’s the plot. It’s a pretty straightforward intrigue (cue the polite laughing), until you bring the watcher into play. He is initially keen to incriminate the playwright and move up a bit in the world, but eventually is taken over to the playwright’s side. It is really amazing to watch the watcher (named Wiesler) waver on the edge, and eventually make the point of no return. There is a huge parade of recurring images, motifs, and nuanced scenes that really make the movie profound, though I still couldn’t tell you what it means.

The colorlessness of the background (especially Wiesler’s life) brings out the vibrant color in the playwright’s circle of artist friends. It made me think of Ernest Hemingway, and Pablo Picasso, Ezra Pound, James Joyce, Gertrude Stein, and F. Scott Fitzgerald all in Paris in the 1920’s; and of Siegfried Sassoon and Ivor Gurney and Julian Grenfell all in the trenches of Europe during the Great War. It made me think of Thoreau and Emerson in the Transcendentalist Club of Massachusetts, and of the Inklings of Oxford, U. K.. The strange and passionate and altogether unreasonable camaraderie that artists have with each other was painted in beautiful, soft watercolor.

There is an “ish” amount of nudity and sex in the film (which is rated “R” for “some sexuality/nudity,” though the actual amount can only be determined by your own personal taste. I say there’s a lot; my sister says not so much), which is the only downside, and the only reason why I might hesitate to recommend this film to someone, and why I will likely not watch it again for a very long time myself. I won’t venture to say whether the movie would be made better or worse if some of that hadn’t been there. I’ll only say that for my sometimes Puritanical viewing pleasure, I wish the amount of steaminess had been somewhat reduced.

Through all this, I still can’t quite decide what it all means. It’s not a cautionary tale about the effects of monitoring people. It’s not really a tale of revolution and civil disobedience. I don’t even think it’s about relying on your own estimations (as opposed to those dictated by the State) of right and wrong. Is it the story of a lonely man living vicariously through the people he listens to? Or is it about how real poetry and real art can truly and actually touch a person deep in their soul and cause them to change?

Whatever it is, it is well worth watching.